Novel Non-Pyrophoric t- and n-Butyllithium Formulations for Chemical Synthesis

Novel non-pyrophoric, bench-stable formulations of tert-Butyllithium (t-BuLi) and n-Butyllithium (n-BuLi) have been developed to solve longstanding pyrophoricity concerns. This was achieved by replacing the small-chain hydrocarbon solvents in the traditional reagents with formulated oligomeric hydrocarbon solvents like poly-α-olefin (PAO). The non-pyrophoric nature of these formulations was demonstrated using EPA’s SW-846 Test Method 1050. Through extensive scope exploration, their effectiveness was demonstrated in the context of numerous reactions, including C-H lithiations, nucleophilic substitutions, SNAr, addition reactions, and halogen exchanges. Based on these evaluations, their reactivity is well-preserved or marginally enhanced compared to their pyrophoric variants. Notably, these formulations are compatible with traditional lithiation additives like KOtBu or TMEDA.

Section Overview

Introduction

Organolithiums play a pivotal role in modern chemical synthesis by facilitating a wide array of transformations as bases,1–3 nucleophiles,1 coupling partners,4–6 or polymerization initiators.1,7 Owing to their versatile reactivity, they are extensively used across various industries8,9 including pharmaceuticals,1,10,11 chemicals, 9,11 polymers, 1,11,12 and agrochemicals. 1,11 In the context of organic synthesis, t-butyl and n-butyl lithium stand as the most used organolithiums.

Despite their extensive applications, these reagents pose significant safety risks due to their inherent pyrophoricity and extreme sensitivity towards air and moisture.13–15 Commercially, these reagents are available as solutions in respective hydrocarbon solvents with fixed molarity, facilitating their easier handling. However, the hydrocarbon solvents typically used, such as hexane or pentane, have relatively low flash points, heightening safety concerns due to the combined risks of the reagent’s pyrophoricity and the high combustibility of these solvents.

Figure 1. Comparison of organolithium reagents:

a) Traditional reagents (t-BuLi, n-BuLi) pose safety, handling, and pyrophoric risks.

b) New methods (gelation, eutectic solvents, long-chain hydrocarbons) improve scope and stability but add challenges.

c) PAO-formulated organolithiums are non-pyrophoric, easy to handle, shelf-stable (under refrigerated conditions), and similarly reactive.

Over the past two decades, numerous incidents involving organolithium reagents have resulted in irreversible damage to research facilities and, tragically, the loss of researchers’ lives.¹⁶ ¹⁷ As a result, strict safety protocols are in place for the safe handling of these compounds, including, but not limited to, the use of fume hoods, appropriate personal protective equipment, and extensive trainings to mitigate risks of accidental exposure.¹³ ¹⁸ ¹⁹ Additionally, traditional organolithium solutions are inherently unstable and degrade over time,⁸ ²⁰ ²¹ requiring chemists to manually titrate each batch to determine its exact molarity before use or disposal, in accordance with standard operating procedures (Figure 1a).²⁰

In recent years, extensive efforts have been made to mitigate the pyrophoric hazards of conventional organolithium reagents.⁵ ²³-²⁷ These efforts focus on developing alternative delivery methods that avoid the use of problematic organic solvents. Broadly, the approaches fall into three categories: organogels,²⁴ deep eutectic solvents,⁵ ²⁵ and oligomeric hydrocarbon solvents (Figure 1b).²³ ²⁶ The organogel strategy, for example, uses organogelators—self-assembling materials that form gels in organic solvents. These vesicle-like structures allow the encapsulation of small soluble molecules and serve as promising media for conducting reactions.²⁴

Evaluating Delivery Systems: Gels, Deep Eutectic Solvents, and Oligomeric Hydrocarbons

Incorporating organolithium reagents into gels can offer solid-like handling, potentially improving stability against air and moisture while simplifying reagent use.²⁴ Smith and co-workers demonstrated this concept with phenyl- and n-butyllithium using hexatriacontane as a gelator.²⁴ However, practical application or extensive adoption remains limited due to poor air stability, high gelator loadings (≥10 wt%), and narrow reagent compatibility (mainly PhLi and n-BuLi). Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) are a class of ionic liquids distinguished by their ability to form eutectic mixtures consisting of two or three components. Typically, these mixtures comprise Lewis or Brønsted acids and bases, encompassing a diverse range of anionic and/or cationic species. ²⁸.²⁸

Hevia and co-workers showed that DESs can serve as reaction media for organolithiums, reducing hydrolysis and side reactions even under open-air conditions.²⁵ ²⁷ Similarly, Capriati and co-workers used an NaCl/H₂O eutectic system to enable sp²–sp³ couplings with moderate yields.⁵ However, beyond these reaction-focused studies, there are no reports demonstrating the storage of organolithiums in DESs. Storage remains highly challenging with conventional DESs, such as choline chloride/H₂O, urea, or glycerol systems, due to their rapid decomposition in protic environments.²⁷

To address these challenges, Bergbreiter’s group investigated hydrocarbon oligomers as alternative solvents for dispersing organolithiums and other organometallic reagents.²³ ²⁶ Specifically, they used poly-α-olefin (PAO) derivatives as the bulk solvent.²³ ²⁶ Despite promising results on non-pyrophoricity, adoption has been limited, this could be due to two main issues: (1) high viscosity - often exceeding 8.2 cP - which hampers handling in batch reactors, flow systems, and automated liquid handlers;²⁹ ³⁰ and (2) non-scalable synthesis, requiring PAO purification with polar solvents and complete removal of low-boiling hydrocarbons like hexane or pentane, steps that raise safety concerns at scale.²³ ²⁶

After careful evaluation of these technologies, we opted to develop the next generation of non-pyrophoric, organolithium reagents by focusing on the solution phase rather than gelation or eutectic systems. This solution-phase approach offers key advantages, including simplified reagent handling and controlled addition, critical for organolithium reactions. Due to concerns with traditional hydrocarbon solvents, we followed the route of Bergbreiter`s group by replacing them with oligomeric hydrocarbons such as poly-α-olefin (PAO) or heavier alternatives. Notably, PAO-based solvents are non-volatile, exhibit low oxygen solubility, and possess high flashpoints, features that are highly desirable for preparing organolithium reagents.³¹ Our goal is to exploit these properties while addressing challenges in reagent stability, viscosity, reactivity, and compatibility with automated workflows (e.g., liquid handlers) through meticulous formulation (Figure 1c).

Results and Discussion: Non-Pyrophoric t-BuLi and n-BuLi Formulations

To develop non-pyrophoric, bench-stable, and easily handleable organolithium solutions, we began by selecting t-BuLi as a benchmark reagent and commercially available PAO as the dispersion medium. Our initial goal was to optimize the solution’s viscosity to allow easy transfer via syringe or cannula. The viscosity of pure PAO was measured at 12.1 cP, well above the desirable range of <4 cP, posing practical challenges for routine reagent handling.

We prepared a 1.7 M t-BuLi solution using our novel formulation, which exhibited a viscosity within the desirable range. To assess its spontaneous combustibility we followed the EPA’s SW-846 Test Method 1050.³² According to this method, a liquid is considered non-pyrophoric if it shows no ignition in two tests: (1) exposure to open air and (2) contact with filter paper. In the first test, 5 mL of the solution was placed in a porcelain cup at room temperature under ambient air and observed for 5 minutes. No ignition or charring occurred. This outcome was confirmed in five repeated trials.

The filter paper test yielded results consistent with the open-air test, further confirming the non-pyrophoric nature of our formulation. To push the limits, we performed a qualitative test (under ambient open-air conditions at 24 °C) to determine how our PAO formulation behaved once exposed to water. By contrast, when conventional t-BuLi reagents are exposed to water they ignite spontaneously. When drops of our PAO formulation were added to water, we observed a slow reaction with the formation of an oily droplets and no spontaneous ignition. This observation, along with previous studies, clearly demonstrates that our PAO formulations offer a lower risk and non-pyrophoric alternative to traditionally hazardous t-BuLi solutions.

Building on this approach, we prepared the novel formulation of n-BuLi, one of the most widely used organolithiums, with a 2.5 M concentration and comparable viscosities of traditional n-BuLi in hexane. The solution’s non-pyrophoricity or non-spontaneous ignition was confirmed using EPA’s SW-846 Test Method 1050.³²

Chemical Reactivity of Formulated Organolithium Reagents

Having developed non-pyrophoric, easily handleable formulations of n-butyl and t-butyl lithium, our investigation pivoted towards assessing their chemical reactivity.

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether these novel formulations maintain or surpass the chemical efficacy of traditional organolithium reagents in facilitating various organic transformations. Considering the key rationale on the impact of solvation on the reagent’s nucleophilicity and basicity,33 we wanted to ensure that our formulations did not undermine their basic chemical functionality. To address this, we systematically examined the activity of these novel formulations in a range of organic reactions typically enabled by such reagents. These reactions included C-H lithiations, nucleophilic aromatic substitutions (SNAr), nucleophilic additions or substitutions, and halogen exchanges. Our evaluations began with the n-BuLi formulation, and we focused on three key reactivity contexts: 1) nucleophilicity, 2) halogen exchanges, and 3) basicity through C-H lithiations, with the aim of determining its comparative/improved effectiveness against traditional n-BuLi in hexane (Figures 2A to 2C).

Initial studies on nucleophilicity involving additions to aldehydes demonstrated excellent yields of secondary alcohols (Figure 2A: 1a, 1b), akin to those achieved with traditional solutions, although substrate 1c did exhibit some undesirable side reactions under both conditions. While isolating the tertiary phosphines, we made sure to use the HBF4 salt strategy to avoid the potential yield discrepancies stemming from the phosphine decompositions (1d, 1e, 1f). The reaction yields ranged from 74% to 88%, which paralleled those of traditional reagents. Further, SNAr reactions with 2-chloropyridine (1i) and an AlPhos key intermediate (1j) yielded 84% and 89%, respectively. In the context of SN2 reactions, a substituted benzyl bromide and an ethyl phenyl bromide were used as substrates, and the desired products were isolated with 70% and 73% yields, demonstrating the efficacy of our novel formulations in various contexts of nucleophilic reactions (1g, 1h).

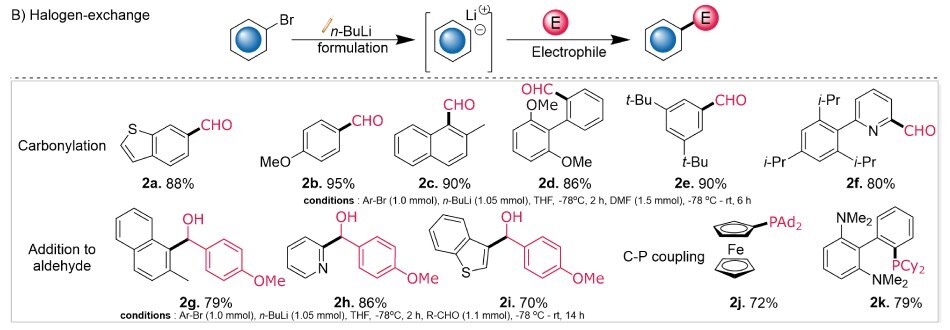

Additionally, we expanded the scope of our exploration to halogen-exchange reactions, where n-BuLi is extensively used. The lithiated halogen precursor was quenched with DMF for carbonylations, or aldehydes to obtain secondary alcohols, or chlorophosphines to obtain tertiary phosphines. Substrate compatibility was impressive for carbonylation reactions, with reaction yields ranging from 80-95% (Figure 2B: 2a-2f). Further, the efficacy of halogen–lithium exchange was evaluated using 1-bromo-2-methylnaphthalene, 2-bromopyridine, and 3-bromobenzothiophene, followed by quenching with p-anisaldehyde. The resulting secondary alcohols (2g–2i) were isolated in good to excellent yields (70–86%).

Notably, this technology was extended towards synthesizing ligands like CPhos (2k) and FcPAd2 (2j) by reacting corresponding nucleophiles with chlorophosphines (PCy2Cl or Ad2PCl).

Next, the basicity of the newly formulated n-BuLi solution was tested in numerous C-H lithiation reactions. In the initial studies, several key ligand precursors were synthesized following literature reports.34,35 Buchwald’s biaryl ligands SPhos and RuPhos precursors were synthesized with lithiating dimethoxy or di-isopropxy benzene and quenched with 1-bromo-2-chlorobenzene.34,35 The desired brominated biaryls 3a and 3b (Figure 2C) were isolated in 79 and 75% yields, respectively. These yields were comparable with the literature reports (3a 77% and 3b 73%).35,36

Figure 2A.Nucleophilicity studies with n-BuLi formulations: aldehyde additions forming secondary alcohols (1a–1c), HBF4-protected phosphines from C–P couplings (1d–1f), SNAr (1i–1j), and SN2 reactions (1g–1h).

Figure 2B.Diagram evaluating efficacy of halogen–lithium exchange through carbonylation (2a-2f; 80-95%), addition to aldehydes (2g-2i), and C-P couplings (2j, 2k).

Figure 2C.Diagram evaluating the basicity of formulated n-BuLi via C–H lithiation to synthesize brominated aromatics (3a-3c), and Phosphine ligands (3d, 3e).

Dibromoferrocene (3c) was synthesized by lithiating ferrocene with n-BuLi and TMEDA, followed by quenching with 1,2-dibromotetrachloroethane.³⁷ Notably, the comparable yields to literature reports demonstrate that our formulations are compatible with activators and stabilizers like TMEDA, and solvation with PAO did not hamper the desired level of reactivity.³⁷ We further validated the effectiveness of our n-BuLi formulation by synthesizing commonly used ligands such as dppf and BippyPhos with yields similar to those reported in the literature (3d, 3e).³⁸ ³⁹ Together, these results show that our novel n-BuLi formulation matches the reactivity of traditional solutions while enabling improved chemical handling, making it a practical and non-pyrpophoric alternative for standard synthetic applications.

Similarly, we broadened the reactivity scope of our novel "non-pyrophoric" t-BuLi formulation by examining its basicity and nucleophilicity in a series of reactions.

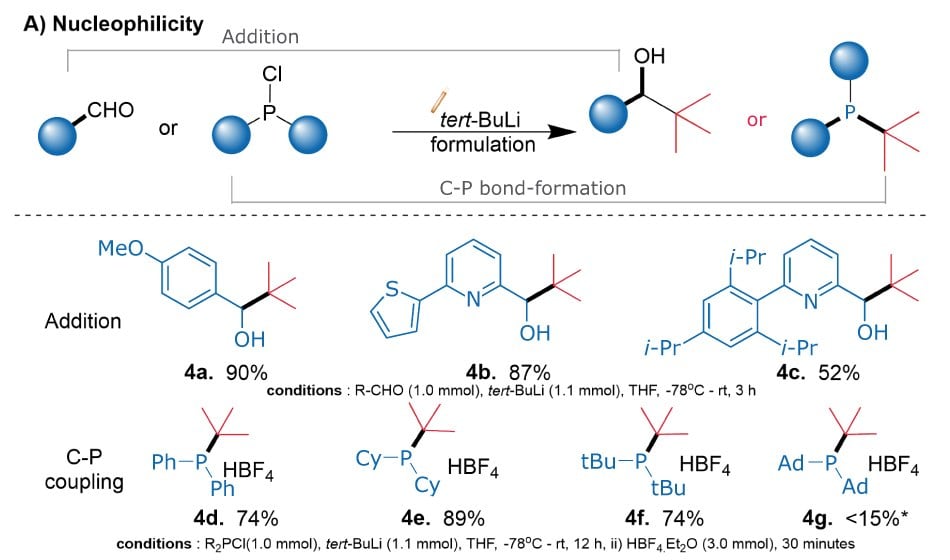

The primary focus was to evaluate the formulation's 1) nucleophilicity through addition reactions 2) reactivity towards halogen exchange reactions, and 3) basicity through C-H lithiation reactions (Figures 3A to 3C). In nucleophilic additions to aldehydes, substrates 4a and 4b (Figure 3A) yielded excellent yields of desired products, while the aldehyde precursor 4c resulted in only moderate yields due to side reactions. Further, the reactions with chlorophosphines proceeded smoothly, and the desired products were isolated as HBF4 salts to avoid their potential decompositions (4d-4f).

Figure 3A.Diagram showing the nucleophilicity of the non-pyrophoric t-BuLi formulation with addition to aldehydes (4a-4c), and C-P couplings (4d-4g).

Figure 3B.Diagram showing t-BuLi halogen exchange yielding carbonylated aromatics (2a, 2d, 2e) and adamantly APhos (5a)

Figure 3C.Diagram of C–H lithiation under Schlosser-type conditions to synthesize phosphino ferrocenes (2j, 6a) and bromoferrocene (6b).

However, the reaction with chloro-di-adamantyl phosphine showed less than 15% conversion to the desired product (4g) after 20 hours, likely due to significant steric hindrance. Halogen exchange reactions were studied by quenching the resulting carbanion with DMF for carbonylation (Figure 3B: 2a, 2d, 2e) or with chlorophosphine for phosphination (5a). Additionally, C–H lithiation under Schlosser-type conditions was used to synthesize adamantyl- and di-tert-butyl phosphino ferrocenes (Figure 3C: 2j, 6a), as well as bromoferrocene (6b), with moderate to excellent yields.

Conclusions: Advancing Chemical Synthesis with Non-Pyrophoric Organolithiums

Overall, we have developed non-pyrophoric, easily handleable, and bench-stable organolithium formulations, addressing the longstanding pyrophoricity concerns associated with traditional organolithium reagents. This is achieved by replacing conventional hydrocarbon solvents with the formulated oligomeric hydrocarbon solvent PAO. The non-pyrophoricity of our formulations was confirmed with EPA’s SW-846 Test Method 1050.

Additionally, our studies extending to chemical reactivity have shown that these novel formulations maintain, and in some cases improve, the efficacy of organolithium reagents in a variety of reactions, including C-H lithiation, nucleophilic substitutions, SNAr, addition, and halogen exchanges. These novel formulations are also effective when combined with various lithiation additives like KOtBu or TMEDA.

Related Products

Response not successful: Received status code 500

1-20

21-39

To continue reading please sign in or create an account.

Don't Have An Account?