How Does the Diffusive Sampler Work? Why is it so Special?

How Does the Diffusive Sampler Work?

The diffusive sampler is a closed box, usually cylindrical. Of its two opposite sides, one is “transparent” to gaseous molecules which cross it, and are adsorbed onto the second side. The former side is named diffusive surface, the latter is the adsorbing surface (marked with S and A in the figure).

In the diffusive sampler, the adsorbing and the diffusive surfaces are two opposing plane of a closed box. Driven by the concentration gradient, the gaseus molecules (coloured in the figure) pass through the diffusive surface and are trapped from the adsorbing surface.

Driven by the concentration gradient dC/dl, the gaseous molecules cross S and diffuse towards A along the path l, parallel to the axis of the cylindrical box. The molecules, which can be trapped by the adsorbing material, are eventually adsorbed onto A according to the equation:

where dm is the adsorbed mass during time dt and D is the diffusion coefficient. Let C be the concentration at the diffusive surface and C0 the concentration at the adsorbing surface, the integral of [1] becomes

If the concentration at the adsorbing surface is negligible, the equation can be approximated to

Q is the sampling rate and has the dimensions of a gaseous flow (if m is expressed in μg, t in minutes and C in μg·l-1, Q is expressed in l·min-1).

Therefore, if Q is constant and measured, to calculate the ambient air concentration you need only to quantify the mass of analyte trapped by the adsorbing material and to keep note of the time of exposure of the diffusive sampler.

To improve the analytical sensitivity the collected mass m should be increased by enlarging Q. As D is a constant term, one can only try to improve the S/l ratio, namely the geometrical constant of the sampler. Unfortunately, in the common axial simmetry sampler, if S is enlarged, the adsorbing surface A must be enlarged too, in order to keep the two parallel surfaces at a fixed distance. Since the analytes can be recovered from the axial sampler only by solvent extraction, any increase of A lead to a proportional increase of the extraction solvent volume, thus the improvement of Q is canceled out by the effect of dilution.

The value of distance l could also be reduced, but under the critical value of about 8 mm the diffusion law is no longer valid in the case of low air velocity values, since adsorption rate becomes higher than supplying rate of analyte molecules at the diffusive surface.

Cannot we improve Q then?

The answer is to improve the sampler geometry to a radial design. From this idea the radiello sampler has been developed, its cylindrical outer surface acting as diffusive membrane: the gaseus molecules move axially parallel towards an adsorbent bed which is cylindrical too and coaxial to the diffusive surface.

When compared to the axial sampler, radiello shows a much higher diffusive surface without increase of the adsorbing material amount. Even if the adsorbing surface is quite smaller then the diffusive one, each point of the diffusive layer faces the diffusion barrier at the same distance.

Section of radiello.

Diffusive and adsorbing surfaces are cylindrical and coaxial: a large diffusive surface

faces, at a fixed distance, the small surface of a little concentric cartridge.

As S=2πrh (where h is the height of the cylinder) and the diffusive path is as long as the radius r, we can then express equation [1] as follows

The integral of equation [4] from rd (radius of the diffusive cylindrical surface) to ra (radius of the adsorbing surface) becomes

the ratio

is the geometrical constant of radiello. The calculated uptake rate [5] is therefore proportional to the height of the diffusive cylinder and inversely proportional to the logarithm of the ratio of diffusive vs adsorbing cylinder radii.

While ra can be easily measured, rd can only be calculated by exposure experiments. Actually the diffusive membrane has been designed with a thick tubular microporous layer. The actual diffusive path length is therefore

much longer than the distance among the diffusive and adsorbing surfaces due to the tortuosity of the path through the pores. A diffusive cylinder of external diameter 8 mm, thickness 1.7 mm and average porosity of

25 μm, coupled to an adsorbing cartridge with radius 2.9 mm creates a diffusive path of 18 mm instead of the straight line path estimation of (8-2.9) = 5.1 mm.

The sampling rate Q is function of diffusive coefficient D, which is a thermodynamic property of each chemical substance. D varies with temperature (T) and pressure (p); therefore also the sampling rate is a function of those variables according to

Q values that will be quoted in the following have been measured at 25 °C and 1013 hPa. As a consequence, they should be corrected so as to reflect the actual sampling conditions.

The correction of Q for atmospheric pressure is usually negligible since its dependence is linear and very seldom we face variations of more than 30 hPa about the average value of 1013 hPa. In the worst case, if corrections for pressure are ignored you make an error of ±3%, usually it is within ±1.5%.

On the other hand, Q depends exponentially on temperature variations, therefore more relevant errors can be introduced if average temperature is significantly different from 25 °C. Moreover, when chemiadsorbing cartridge are used kinetic effects (variations of reaction velocities between analyte and chemiadsorbing substrate) can be evident, apart from thermodynamic ones (variation of D).

It is therefore very important to know the average temperature in order to ensure accuracy of experimental

data. how you can perform on-field temperature measurements on page B3.

Even if some cartridges adsorb large quantities of water when exposed for a long time in wet atmosphere, generally this does not affect sampling by radiello. Some consequences, neverthless, can sometimes be felt on the analysis. As an example, a very wet graphitised charcoal cartridge could generate ice plugs during cryogenic focusing of thermally desorbed compounds or blow out a FID flame.

It is therefore important to protect radiello from bad weather. page B1 how this can be easily done.

Why is radiello so Special?

The diffusive sampling does not involve the use of heavy and encumbering pumping systems, does not have energy

power supply problems, does not require supervision, is noiseless, is not flammable and does not represent an explosion hazard, can be performed by everybody everywhere and with very low costs.

Moreover, it is not subject to the breakthrough problem, which can be serious when active pumping is performed.

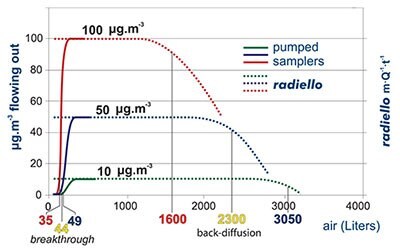

In pumped sampling the adsorbed compound behaves as a chromatographic peak (top): air flow displaces it along the adsorbent bed and its concentration is distributed as a gaussian function. Eventually, the compound comes out from the opposite end. When its concentration in the outlet air is 10% of the concentration in the sampled air we say that the breakthrough has been reached or, with a misleading expression, that the tube has been saturated. Any further pumping leads to a loss of analyte and a consequent underestimation of the environmental concentration. The extent of this phenomenon depends weakly on the concentration of target compound but rather on the value of air flow, the overall sampling volume and the chemical compound involved.

In the graph the case of benzene is displayed, sampled at 25 °C onto an activated charcoal adsorbent bed of the same volume of a code 130 (Product No. RAD130) radiello cartridge. The breakthrough is reached after 35, 44 or 49 liters of sampled air depending on benzene concentration in air (10, 50 or 100 μg·m-3 respectively).

An apparently similar phenomenon is shown by radiello also. In this case, however, we cannot speak of breakthrough, since no actual air flow is involved, but rather of backdiffusion. This consists of a decrease of the value of m·Q-1·t-1 (which is equal to the measured concentration (equation [3] above). This term is constant and equal to the actual concentration until the adsorbed mass of analyte is far from the maximum amount allowed by the adsorbing medium

capacity. The extent of backdiffusion depends on concentration and exposure time but a decrease of 10% in them·Q-1·t-1 term is observed along with equivalent sampling volumes of magnitude bigger than those seen before: 1600, 2300 and 3050

liters at the concentration of 10, 50 and 100 μg·m-3.

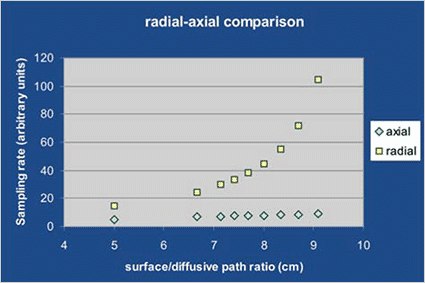

For a traditional axial symmetry sampler the uptake rate increases linearly with tha ratio of diffusive surface vs diffusive path length, while for the radial symmetry sampler, the corresponding increase is exponential. This means that, let the diffusive surface vs diffusive path length ratio be 8:1, for the axial sampler the uptake rate value is 8 (regardless of dimensions) while for the radial one it is 45.

Why diffusive sampling has not been so extensively adopted up to now? This is due to the fact that the traditional axial symmetry sampler has generally poor sensitivity and reproducibility because of the limits set by its geometry. On one side, uptake rate values are generally low, on the other, they often vary depending on environmental conditions.

These limitations have been overcome by radiello.

By virtue of radial symmetry, uptake rate is:

- High, since it does not vary linearly but exponentially with the ratio diffusive surface vs diffusive path length (quation [5]). With the same dimensions, radiello’s uptake rate is at least three times higher than that of any axial diffusive sampler.

- Constant, due to the great adsorbing capacity of the adsorbing cartridge;

- Reproducible, by virtue of the stiffness of the diffusive membrane and the cartridge and of the close tolerances characterizing all the components of radiello.

- Invariable with air speed, due to the tortuosity of the diffusive path inside the microporous diffusive cylindrical surface.

- Precisely measured, because it is not calculated but experimentally measured in a controlled atmosphere chamber in a wide range of concentration, temperature, relative humidity, air speed conditions and with or without interferents....

Moreover, radiello

- Is able to work properly also with bad weather conditions due to the water-repellent diffusive body.

- Has blank values lower than three times the instrumental noise due to the complex conditioning procedures of the bulk adsorbing (or chemiadsorbing) materials and to the repeated quality controls along the whole production.

- Has low detection limits and high adsorbing capacities that allow exposure time duration from 15 minutes to 30 days and concentration measurements from 1 ppb to over 1000 ppm.

- Offers high precision and accuracy over a wide range of exposure values.

- Allows thermal desorption and HRGC-MS analysis without interferents.

- Is suited to the sampling of a vast range of gaseous pollutants.

- Is though and chemically inert, being made of polycarbonate, microporous polyethylene and stainless steel.

- Is indefinitely reusable in all of its components apart from the adsorbing cartridge; the latter can be recovered if thermal desorption is employed.

- Comes from the efforts of one of the main European scientific research institutions that produces it directly by high technology equipment and continuously submits it to severe tests and per forms research and development in its laboratory in Padova.

Materials

Response not successful: Received status code 500

To continue reading please sign in or create an account.

Don't Have An Account?